'Big Short' Burry's depreciation gripe shines spotlight on big tech cos' profits

Big Tech’s ability to churn out ever-increasing profits has underpinned investors’ ongoing enthusiasm for the stocks regardless of their soaring valuations. But what if those numbers are overstated?

That’s the question famed investor Michael Burry raised in a much-discussed social media post this week. The head of Scion Asset Management, who’s best known for his bet against the US housing market before the 2008 global financial crisis and recently terminated his hedge fund’s registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission, suggested that the lengthening depreciation schedules for computing gear from technology behemoths like Meta Platforms Inc. and Alphabet Inc. enables them to artificially pad their earnings growth.

These kinds of accounting moves aren’t secrets and most investors are betting that the hundreds of billions of dollars being spent on chips and other data center equipment will eventually pay off. Shares of the four biggest spenders on artificial intelligence infrastructure — Meta, Alphabet, Amazon.com Inc. and Microsoft Corp. — are in the green this year.

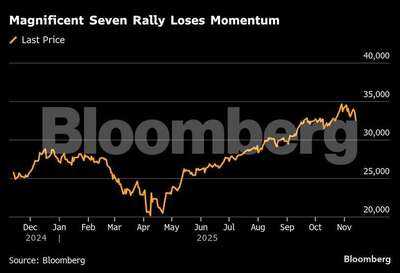

But the involvement of Burry, who’s closely followed in the investment community thanks to his starring role in the book The Big Short, is putting a spotlight on the risks of that massive spending. Meta, for example, is up just 3% in 2025, far below the 18% rise in the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 Index, and the stock is down 18% in the second half of the year, putting it among the index’s 25 worst performers. By contrast, Alphabet has soared 46% this year, while Microsoft has jumped 19%.

“We’re in a period where we’re going from having AI hype to needing AI proof,” said Anthony Saglimbene, chief market strategist at Ameriprise Financial Services Inc.

The issue is how quickly depreciating assets like graphics processing units and servers lose value. In recent years, most Big Tech companies have lengthened the so-called useful life estimates for such equipment, reducing non-cash charges that weigh on net income. Earlier this year, Meta extended its useful life estimates from four-to-five years to five-and-a-half years, estimating that the change would reduce its 2025 depreciation expense by $2.9 billion.

Microsoft and Alphabet have both made similar moves in recent years, saying they’ve managed to wring more use out of the equipment.

“Companies are always upgrading their servers and networking gear and chips, so it isn’t a new factor, but we haven’t seen it at this kind of scale before,” Saglimbene said. “That’s what is making investors nervous.”

Whether the longer time-line is appropriate is difficult to judge, according to Stephen Glaeser, associate professor of accounting at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School. Skeptics argue that depreciation should accelerate as chipmakers like Nvidia Corp. release chips at a faster pace. That was the view taken by Amazon, which in February shortened the useful life of server equipment to five years from six.

Representatives for Amazon and Microsoft declined to comment. Meta and Alphabet didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Microsoft Chief Executive Officer Satya Nadella discussed the importance of continually buying new chips and making improvements to get more use out of such short-lived assets on the company’s fiscal first-quarter earnings call last month.

“You continually modernize and depreciate it. And that means you also use software to grow efficiency,” he said in response to a question about generating sufficient returns on investments.

The debate is more important than ever as the pace of capital expenditures on computing infrastructure continue to accelerate. The four biggest spenders are projected to boost combined capex by about 40% to $460 billion in the next 12 months, with much of that going to computing equipment, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

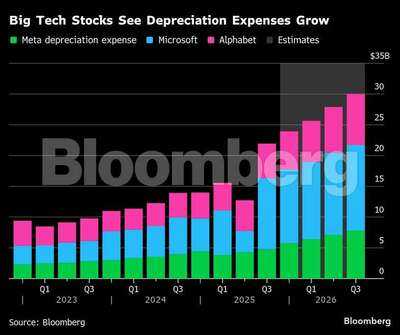

Depreciation expenses are skyrocketing even with the accounting moves. Alphabet, Microsoft and Meta combined for about $10 billion in depreciation costs in the final quarter of 2023. In the quarter that just ended in September the figure rose to nearly $22 billion. By this time next year, analysts expect it to be almost $30 billion.

Still, the group delivered third-quarter profits that handily beat Wall Street expectations. With results from Nvidia due next week, earnings for the so-called Magnificent Seven, which also includes Apple Inc. and Tesla Inc., are on pace to rise 27% from a year ago, nearly twice the 14% expansion that was projected at the start of earnings season, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence.

Those kinds of profits outweigh any qualms about things like depreciation costs, according to Phil Blancato, chief market strategist at Osaic, which has more than $700 billion in assets under management.

“The money they’re spending is very stimulative for future earnings, and that’s the point that is being missed,” Blancato said. “There’s just no reason yet to be concerned about their ability to grow.”

That’s the question famed investor Michael Burry raised in a much-discussed social media post this week. The head of Scion Asset Management, who’s best known for his bet against the US housing market before the 2008 global financial crisis and recently terminated his hedge fund’s registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission, suggested that the lengthening depreciation schedules for computing gear from technology behemoths like Meta Platforms Inc. and Alphabet Inc. enables them to artificially pad their earnings growth.

These kinds of accounting moves aren’t secrets and most investors are betting that the hundreds of billions of dollars being spent on chips and other data center equipment will eventually pay off. Shares of the four biggest spenders on artificial intelligence infrastructure — Meta, Alphabet, Amazon.com Inc. and Microsoft Corp. — are in the green this year.

But the involvement of Burry, who’s closely followed in the investment community thanks to his starring role in the book The Big Short, is putting a spotlight on the risks of that massive spending. Meta, for example, is up just 3% in 2025, far below the 18% rise in the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 Index, and the stock is down 18% in the second half of the year, putting it among the index’s 25 worst performers. By contrast, Alphabet has soared 46% this year, while Microsoft has jumped 19%.

“We’re in a period where we’re going from having AI hype to needing AI proof,” said Anthony Saglimbene, chief market strategist at Ameriprise Financial Services Inc.

The issue is how quickly depreciating assets like graphics processing units and servers lose value. In recent years, most Big Tech companies have lengthened the so-called useful life estimates for such equipment, reducing non-cash charges that weigh on net income. Earlier this year, Meta extended its useful life estimates from four-to-five years to five-and-a-half years, estimating that the change would reduce its 2025 depreciation expense by $2.9 billion.

Microsoft and Alphabet have both made similar moves in recent years, saying they’ve managed to wring more use out of the equipment.

“Companies are always upgrading their servers and networking gear and chips, so it isn’t a new factor, but we haven’t seen it at this kind of scale before,” Saglimbene said. “That’s what is making investors nervous.”

Whether the longer time-line is appropriate is difficult to judge, according to Stephen Glaeser, associate professor of accounting at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School. Skeptics argue that depreciation should accelerate as chipmakers like Nvidia Corp. release chips at a faster pace. That was the view taken by Amazon, which in February shortened the useful life of server equipment to five years from six.

Representatives for Amazon and Microsoft declined to comment. Meta and Alphabet didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Microsoft Chief Executive Officer Satya Nadella discussed the importance of continually buying new chips and making improvements to get more use out of such short-lived assets on the company’s fiscal first-quarter earnings call last month.

“You continually modernize and depreciate it. And that means you also use software to grow efficiency,” he said in response to a question about generating sufficient returns on investments.

The debate is more important than ever as the pace of capital expenditures on computing infrastructure continue to accelerate. The four biggest spenders are projected to boost combined capex by about 40% to $460 billion in the next 12 months, with much of that going to computing equipment, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Depreciation expenses are skyrocketing even with the accounting moves. Alphabet, Microsoft and Meta combined for about $10 billion in depreciation costs in the final quarter of 2023. In the quarter that just ended in September the figure rose to nearly $22 billion. By this time next year, analysts expect it to be almost $30 billion.

Still, the group delivered third-quarter profits that handily beat Wall Street expectations. With results from Nvidia due next week, earnings for the so-called Magnificent Seven, which also includes Apple Inc. and Tesla Inc., are on pace to rise 27% from a year ago, nearly twice the 14% expansion that was projected at the start of earnings season, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence.

Those kinds of profits outweigh any qualms about things like depreciation costs, according to Phil Blancato, chief market strategist at Osaic, which has more than $700 billion in assets under management.

“The money they’re spending is very stimulative for future earnings, and that’s the point that is being missed,” Blancato said. “There’s just no reason yet to be concerned about their ability to grow.”

Next Story