'Commission bandh hai': No chairperson, no staff, no help — once a Lifeline for distressed women, Delhi Mahila Aayog now lies defunct

NEW DELHI: For years, women in distress knew the first place to go: Delhi Commission for Women . Walk into Mahila Aayog , and someone will sit across you, calm your nerves, and hear you out. Try that now. At its Vikas Bhawan office, ask the guard for Mahila Aayog and he shrugs without even looking up: “ Bandh hai ” (shut). Climb to the second floor, to double check. The corridor, once filled withvoices and pleas for help, lies abandoned, and an A4 sheet taped by the lift says, “Commission for Women”. The first door is locked. The second, labelled Helpdesk, is locked. The third, Mobile Helpline, too, is locked.

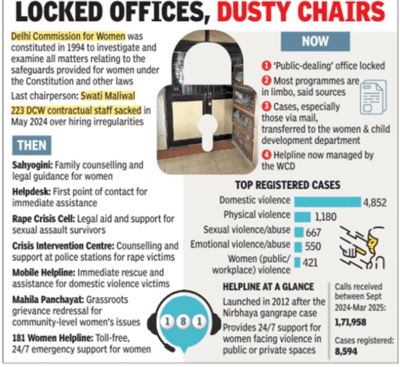

Since Jan 2024, the commission has had no chairperson, and no members since July 2024. In May 2024, Women and Child Development dept ordered removal of 223 contractual staffers over “improper” hiring . The last chairperson, Swati Maliwal , resigned after being elected to the Rajya Sabha in Jan 2024. With leadership gone and staff drastically reduced, the commission has become nonfunctional.

“Delhi govt has given additional charges for DCW and Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights chairpersons to one IAS officer. The govt will take a decision regarding the future course of action soon,” said a Delhi govt official.

The stop-gap arrangement goes against the spirit of Delhi Commission for Women Act, 1994, which mandates that the chairperson nominated by the govt must be an individual deeply committed to the cause of women’s welfare and empowerment.

A former DCW member said having officers holding additional charges as chairpersons is no different from having no chairperson at all.

“These are public-facing institutions that demand fulltime, undivided attention because the cases are very sensitive. An overburdened officer simply cannot provide the leadership, accessibility, or accountability that the commission urgently requires,” she said.

DCW, constituted in 1994 to investigate and examine all matters relating to the safeguards provided for women under the Constitution and other laws, looks at matters ranging from abuse and exploitation to counselling, rescue, and legal assistance for women.

On Thursday morning, one such woman climbed these stairs, only to be redirected to the National Commission for Women. She may have asked where did all the staff go.

Another DCW office does exist. But it functions only as an administrative outpost, pushing case mails to the Women and Child Devel opment Department. No walk-ins. No counselling. No helping hand.

“Now it’s just 8–9 govt officials doing administrative work,” said a source. And it’s showing in the programmes that once defined DCW.

DCW’s moribund status has pulled the plug on several programmes it ran.

Sources said the Helpdesk, the first touchpoint for women seeking in-person support, is gone. The Rape Crisis Cell, created under Delhi high court directions to assist survivors of sexual assault, is silent.

The Crisis Intervention Centres, once recognised by the Delhi Police for counselling rape survivors, have ceased to function.

The Mahila Panchayat, a grassroots grievance redressal platform for women who had nowhere else to turn, has collapsed. And the crucial DCW helpline 181 has been shifted to Women and Child Development dept.

Suhail from Sofia NGO said, “We used to run the Mahila Panchayat. There are two types of women — those educated and those comp letely out of touch. Mahila Panchayat was meant to fill that gap. We had 80 centres in urban villages and backward areas… many cases were pending when they we re shut. It still makes as emotional when we think of how we redirected them to WCD or courts and left them on their own.”

Neha (name changed), from Bhajanpura, recalled how her neighbour’s domestic violence case was handled “so well” two years ago that the woman is now living with dignity. But just two days ago, when Neha returned with a dowry harassment case, she was told, “We have been redirected to WCD or court. Poor families cannot even step outside their lane. Ab kahan jaayenge hum… vo ab aise hi baithi hai . (Now where will we go… she’s still in the same state).”

Another person who monitored the Rape Crisis Cell said, “So many survivors still call us. And all we can say is: we do not work there anymore. The saddest part is that they are not cases — they are lives.”

While almost everything has been without a pulse, the nodal 181 Helpline has been formally transferred to the WCD Department. Launched in 2012 after the Nirbhaya gangrape case, the toll-free Women Helpline 181 provides 24/7 emergency and support services for women facing violence in both public and private spaces. Between September 2024 and March 2025, the helpline recorded 8594 cases, according to data obtained through the Right to Information (RTI) Act.

Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights (DCPCR), too, has had no full-time chairperson since July 2023. An IAS officer is handling the role temporarily as an officiating chairperson. Activists warn this lack of leadership hampers quick action on child rights violations.

An official said the selection process of full-time chairperson and six members of DCPCR is going on and is likely to be finalised soon.

Since Jan 2024, the commission has had no chairperson, and no members since July 2024. In May 2024, Women and Child Development dept ordered removal of 223 contractual staffers over “improper” hiring . The last chairperson, Swati Maliwal , resigned after being elected to the Rajya Sabha in Jan 2024. With leadership gone and staff drastically reduced, the commission has become nonfunctional.

“Delhi govt has given additional charges for DCW and Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights chairpersons to one IAS officer. The govt will take a decision regarding the future course of action soon,” said a Delhi govt official.

The stop-gap arrangement goes against the spirit of Delhi Commission for Women Act, 1994, which mandates that the chairperson nominated by the govt must be an individual deeply committed to the cause of women’s welfare and empowerment.

A former DCW member said having officers holding additional charges as chairpersons is no different from having no chairperson at all.

“These are public-facing institutions that demand fulltime, undivided attention because the cases are very sensitive. An overburdened officer simply cannot provide the leadership, accessibility, or accountability that the commission urgently requires,” she said.

DCW, constituted in 1994 to investigate and examine all matters relating to the safeguards provided for women under the Constitution and other laws, looks at matters ranging from abuse and exploitation to counselling, rescue, and legal assistance for women.

On Thursday morning, one such woman climbed these stairs, only to be redirected to the National Commission for Women. She may have asked where did all the staff go.

Another DCW office does exist. But it functions only as an administrative outpost, pushing case mails to the Women and Child Devel opment Department. No walk-ins. No counselling. No helping hand.

“Now it’s just 8–9 govt officials doing administrative work,” said a source. And it’s showing in the programmes that once defined DCW.

DCW’s moribund status has pulled the plug on several programmes it ran.

Sources said the Helpdesk, the first touchpoint for women seeking in-person support, is gone. The Rape Crisis Cell, created under Delhi high court directions to assist survivors of sexual assault, is silent.

The Crisis Intervention Centres, once recognised by the Delhi Police for counselling rape survivors, have ceased to function.

The Mahila Panchayat, a grassroots grievance redressal platform for women who had nowhere else to turn, has collapsed. And the crucial DCW helpline 181 has been shifted to Women and Child Development dept.

Suhail from Sofia NGO said, “We used to run the Mahila Panchayat. There are two types of women — those educated and those comp letely out of touch. Mahila Panchayat was meant to fill that gap. We had 80 centres in urban villages and backward areas… many cases were pending when they we re shut. It still makes as emotional when we think of how we redirected them to WCD or courts and left them on their own.”

Neha (name changed), from Bhajanpura, recalled how her neighbour’s domestic violence case was handled “so well” two years ago that the woman is now living with dignity. But just two days ago, when Neha returned with a dowry harassment case, she was told, “We have been redirected to WCD or court. Poor families cannot even step outside their lane. Ab kahan jaayenge hum… vo ab aise hi baithi hai . (Now where will we go… she’s still in the same state).”

Another person who monitored the Rape Crisis Cell said, “So many survivors still call us. And all we can say is: we do not work there anymore. The saddest part is that they are not cases — they are lives.”

While almost everything has been without a pulse, the nodal 181 Helpline has been formally transferred to the WCD Department. Launched in 2012 after the Nirbhaya gangrape case, the toll-free Women Helpline 181 provides 24/7 emergency and support services for women facing violence in both public and private spaces. Between September 2024 and March 2025, the helpline recorded 8594 cases, according to data obtained through the Right to Information (RTI) Act.

Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights (DCPCR), too, has had no full-time chairperson since July 2023. An IAS officer is handling the role temporarily as an officiating chairperson. Activists warn this lack of leadership hampers quick action on child rights violations.

An official said the selection process of full-time chairperson and six members of DCPCR is going on and is likely to be finalised soon.

Next Story