Civilisation on the wall: Why graffiti, the epitaph of our times, needs to be preserved

Gauging by the interest generated by the Tamil Brahmi imprimatur left in Egypt by one ancient intrepid Indian traveller named Cikai Korran - perhaps a forebear of the peripatetic Tintin as his first name is reminiscent of the Sanskrit word for tuft of hair - the scrawls on walls that we now routinely deride as 'defacement' will one day become historical marvels. These will be studied and interpreted as rare remnants from the age by when physical writing had disappeared.

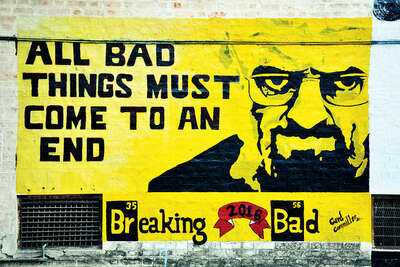

After all, apart from graffiti, we now generate little non-virtual evidence of our current civilisation and thoughts. We don't put pen to paper anymore, print is passe and even brush-to-canvas is giving way to screens. Social media outpourings, brilliant forwards, humour, sarcasm, commentaries, critiques and AI-generated fakes may not survive the obsolescence of the gadgets they are created by and remain confined to. So our era's epitaphs may well be graffiti.

Once this realisation dawns, we all will want to secretly etch our names, emotions and views on real walls instead of just on social media walls. For, it could be the only way to bridge millennia to communicate with people in the future. What they make of our graffiti is another matter, but those maudlin declarations of love, announcements of presence and messily scratched initials, not merely the artsy genre of Banksy, would be civilisational semaphores of our times.

Admittedly though, thoughts of millennial immortality may not have been what motivated Thiru Korran to announce that he had visited an imperial Egyptian necropolis 1,800 years ago. He could not have anticipated the avalanche of questions his scrawls at eight places in Egypt set off, any more than a Shivansh etching his passion for Riya at a popular tourist spot somewhere abroad in 2026 would realise he could trigger excitement and interest in, say, 3026.

And yet the simple phrase "Cikai Korran vara kantan (came and saw)", the Tamil equivalent of the commonest Greek graffiti of the time found at the same Egyptian venues - precursor to the "Kilroy was here" scribbles of World War II - has become the stuff of deep academic discussions and presentations at international conferences by Indian and foreign scholars. They also, of course, indicate that tourism is a far older pastime than most of us realise.

Indeed, the urge to explore and leave personal marks on the canvas of time have been the twin motivators of our species, proved by the thousands of graffiti inscribed by foreigners to Egypt's monuments down the centuries. Their sheer antiquity (the oldest found so far date to the 6th century BCE) indicates how deeply graffiti is ingrained in the human psyche. They are the intellectual heirs of the cave paintings that guide our understanding of prehistoric humans.

The importance of what is hewn into hard, tangible surfaces in a time when most of human information and communication has 'dematerialised' is manifest. Like Cikai Korran's laconic lines or expansive Ashokan edicts, these will be what we are judged by. Positioning, distribution, subject, gender representation and quality of engraving will dictate the future's impression of us; flubs would condemn our era to scorn from generations yet unborn. It is a sobering prospect.

An official rethink on the issue is warranted. Ancient graffiti are lavished with care and scholarly attention while modern ones are subjected to strong cleaning fluids and steep fines for perpetrators, if caught. This discrimination should cease. By dismissing graffiti as visual litter and ordering their effacement, we could be erasing crucial civilisational data of our times. Is there a case for selective preservation based on assessment of probable future relevance?

After all, apart from graffiti, we now generate little non-virtual evidence of our current civilisation and thoughts. We don't put pen to paper anymore, print is passe and even brush-to-canvas is giving way to screens. Social media outpourings, brilliant forwards, humour, sarcasm, commentaries, critiques and AI-generated fakes may not survive the obsolescence of the gadgets they are created by and remain confined to. So our era's epitaphs may well be graffiti.

Once this realisation dawns, we all will want to secretly etch our names, emotions and views on real walls instead of just on social media walls. For, it could be the only way to bridge millennia to communicate with people in the future. What they make of our graffiti is another matter, but those maudlin declarations of love, announcements of presence and messily scratched initials, not merely the artsy genre of Banksy, would be civilisational semaphores of our times.

Admittedly though, thoughts of millennial immortality may not have been what motivated Thiru Korran to announce that he had visited an imperial Egyptian necropolis 1,800 years ago. He could not have anticipated the avalanche of questions his scrawls at eight places in Egypt set off, any more than a Shivansh etching his passion for Riya at a popular tourist spot somewhere abroad in 2026 would realise he could trigger excitement and interest in, say, 3026.

And yet the simple phrase "Cikai Korran vara kantan (came and saw)", the Tamil equivalent of the commonest Greek graffiti of the time found at the same Egyptian venues - precursor to the "Kilroy was here" scribbles of World War II - has become the stuff of deep academic discussions and presentations at international conferences by Indian and foreign scholars. They also, of course, indicate that tourism is a far older pastime than most of us realise.

Indeed, the urge to explore and leave personal marks on the canvas of time have been the twin motivators of our species, proved by the thousands of graffiti inscribed by foreigners to Egypt's monuments down the centuries. Their sheer antiquity (the oldest found so far date to the 6th century BCE) indicates how deeply graffiti is ingrained in the human psyche. They are the intellectual heirs of the cave paintings that guide our understanding of prehistoric humans.

The importance of what is hewn into hard, tangible surfaces in a time when most of human information and communication has 'dematerialised' is manifest. Like Cikai Korran's laconic lines or expansive Ashokan edicts, these will be what we are judged by. Positioning, distribution, subject, gender representation and quality of engraving will dictate the future's impression of us; flubs would condemn our era to scorn from generations yet unborn. It is a sobering prospect.

An official rethink on the issue is warranted. Ancient graffiti are lavished with care and scholarly attention while modern ones are subjected to strong cleaning fluids and steep fines for perpetrators, if caught. This discrimination should cease. By dismissing graffiti as visual litter and ordering their effacement, we could be erasing crucial civilisational data of our times. Is there a case for selective preservation based on assessment of probable future relevance?

Next Story