Amur Falcons Start Epic Africa-Bound Journey From Manipur, IAS Officer Shares Update

The Amur Falcon is a small and agile bird of prey that completes one of the most extraordinary long-distance journeys on the planet. Every year, Amur Falcons migrate more than 20,000 kilometres from their breeding grounds in north-east China, Mongolia and south-east Russia to their wintering areas in southern Africa. This remarkable Amur Falcon migration includes a challenging flight across the Arabian Sea, which is considered one of the toughest continuous flights attempted by any raptor. A major part of their journey depends on their stopover in India, especially in Nagaland and Manipur, where thousands of Amur Falcons in India feed on insects and regain strength before continuing their voyage.

GPS Tracking Reveals New Insights

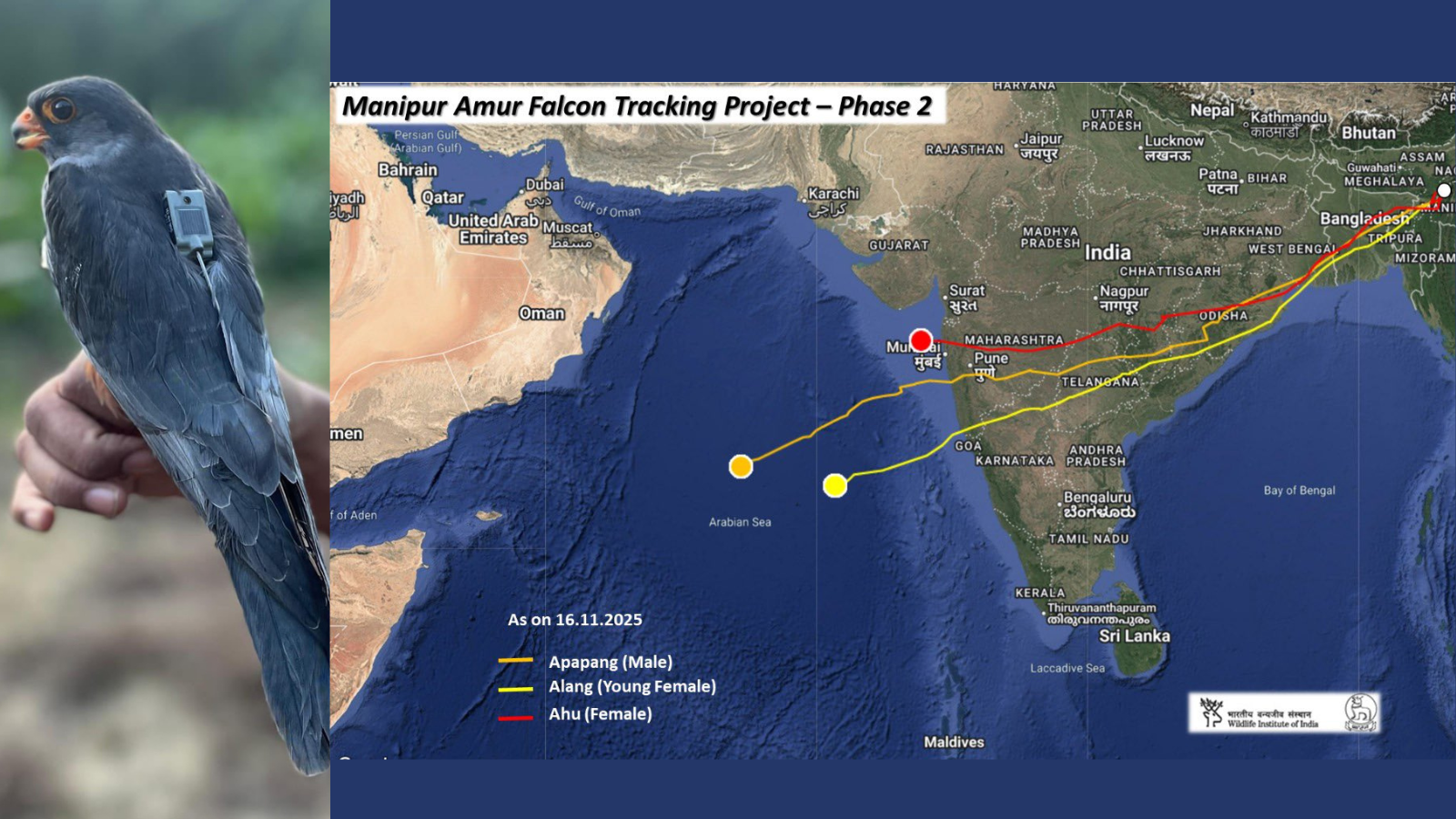

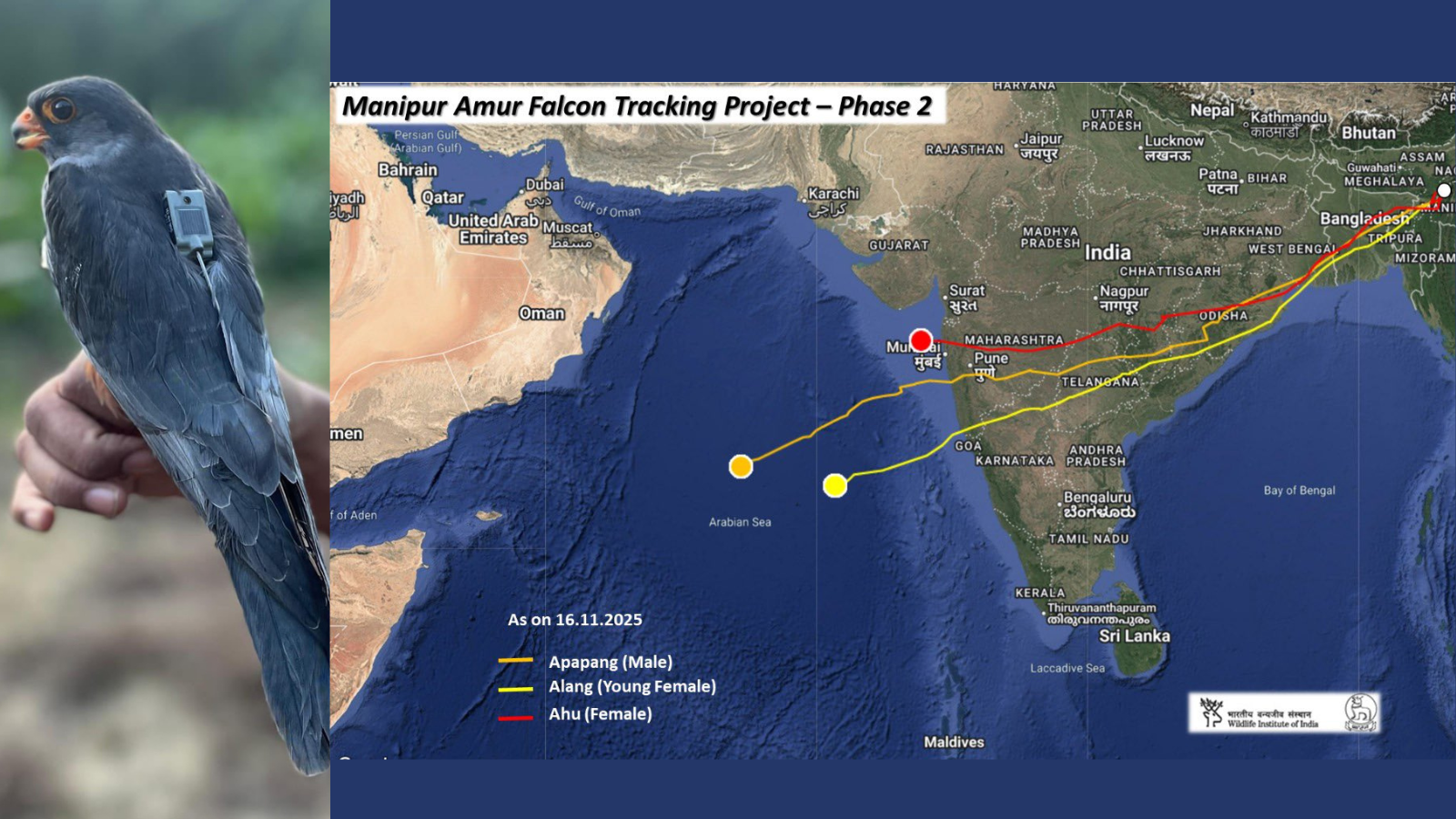

This migration season, at least three GPS tracked Amur Falcons were monitored as they began their journey from India to Africa. The birds were named Apapang (adult male, orange track), Alang (young female, yellow track) and Ahu (adult female, red track). They were tagged on 11 November under the Manipur Amur Falcon Tracking Project by the Wildlife Institute of India. Their tracking data has revealed extraordinary insights into the migration of Amur Falcons and their incredible endurance.

IAS officer Supriya Sahu from Tamil Nadu shared updates on X, highlighting the scale of their journey.

“And the epic journey begins again in all its glory,” she wrote. She added, “Apapang has stunned trackers with an extraordinary non-stop flight, already cutting across central India and now skimming the Arabian Sea, poised for a 3,000 km oceanic crossing to Somalia… These tiny birds barely 150 grams continue to remind us of the sheer wonder of migration, and why India's protection of stopover sites has become a global conservation story. What a wonder!”

She shared images of the tracking device fitted on the birds and also posted a video showing thousands of Amur Falcons taking off together.

The Most Challenging Phase of the Migration

She later shared an update on Sunday when the birds began the toughest phase of their journey.

“All three satellite-tagged Amur Falcons Apapang (male), Alang (young female) and Ahu (female) are now undertaking their daring Arabian Sea crossing . Apapang has already flown nonstop for 76 hours, covering 3100 km at an average of 1000 km per day, aided by strong easterly tailwinds. From here, the journey becomes even more extraordinary as they head towards Somalia on their epic 3000 km oceanic flight.”

The Arabian Sea crossing is known as one of the most demanding flights attempted by any raptor species. It requires enormous energy reserves, the right wind patterns and exceptional stamina.

Every November, Amur Falcons leave their breeding grounds in Russia, China, Korea and Japan and begin their trans equatorial journey to South Africa. Their most important stopover falls in northeastern India, where a decade of conservation work has completely transformed their fate.

From Hunting to Conservation Success

Ten years ago, Amur Falcons were hunted in large numbers in parts of Manipur, Nagaland and Assam. This changed when the Wildlife Institute of India launched its first tracking project in Nagaland in 2013. Today, villages such as Chiuluan in Manipur, which were once hunting zones, have become safe sheltering sites for the birds. Villagers now participate in tagging efforts and have become protectors of the species. Chiuluan became globally recognised when a tagged falcon named Chiuluan 2 successfully flew from Maharashtra across the Arabian Sea to Somalia and then travelled through Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique on its way to Johannesburg.

Why Amur Falcons Choose India

Even though Amur Falcons range across Siberia and East Asia and number more than a million, they choose northeastern India for a very specific reason. The region is rich in termites, which provide the high nutrition needed for the long-distance Amur Falcon migration. This makes India one of the most important stopover points along their migration route.

The story of Amur Falcons, their incredible endurance and India’s conservation success highlights how community participation and dedicated protection efforts can create a global conservation model.

GPS Tracking Reveals New Insights

This migration season, at least three GPS tracked Amur Falcons were monitored as they began their journey from India to Africa. The birds were named Apapang (adult male, orange track), Alang (young female, yellow track) and Ahu (adult female, red track). They were tagged on 11 November under the Manipur Amur Falcon Tracking Project by the Wildlife Institute of India. Their tracking data has revealed extraordinary insights into the migration of Amur Falcons and their incredible endurance.

IAS officer Supriya Sahu from Tamil Nadu shared updates on X, highlighting the scale of their journey.

“And the epic journey begins again in all its glory,” she wrote. She added, “Apapang has stunned trackers with an extraordinary non-stop flight, already cutting across central India and now skimming the Arabian Sea, poised for a 3,000 km oceanic crossing to Somalia… These tiny birds barely 150 grams continue to remind us of the sheer wonder of migration, and why India's protection of stopover sites has become a global conservation story. What a wonder!”

She shared images of the tracking device fitted on the birds and also posted a video showing thousands of Amur Falcons taking off together.

The Most Challenging Phase of the Migration

She later shared an update on Sunday when the birds began the toughest phase of their journey.

“All three satellite-tagged Amur Falcons Apapang (male), Alang (young female) and Ahu (female) are now undertaking their daring Arabian Sea crossing . Apapang has already flown nonstop for 76 hours, covering 3100 km at an average of 1000 km per day, aided by strong easterly tailwinds. From here, the journey becomes even more extraordinary as they head towards Somalia on their epic 3000 km oceanic flight.”

The Arabian Sea crossing is known as one of the most demanding flights attempted by any raptor species. It requires enormous energy reserves, the right wind patterns and exceptional stamina.

Every November, Amur Falcons leave their breeding grounds in Russia, China, Korea and Japan and begin their trans equatorial journey to South Africa. Their most important stopover falls in northeastern India, where a decade of conservation work has completely transformed their fate.

You may also like

- "The world is one family": PM Modi hails Sathya Sai Baba as embodiment of 'Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam'

- West Bengal BLO dies by 'suicide' due to SIR 'workload'

- When Indira Gandhi edited English translation of Rabindranath Tagore's Ekla Chalo Re

- Mitchell Marsh back in Ashes frame after surprise Sheffield Shield return

- "Being a woman, I feel very proud...": JD(U) Leader Komal Singh after NDA's win in Bihar

From Hunting to Conservation Success

Ten years ago, Amur Falcons were hunted in large numbers in parts of Manipur, Nagaland and Assam. This changed when the Wildlife Institute of India launched its first tracking project in Nagaland in 2013. Today, villages such as Chiuluan in Manipur, which were once hunting zones, have become safe sheltering sites for the birds. Villagers now participate in tagging efforts and have become protectors of the species. Chiuluan became globally recognised when a tagged falcon named Chiuluan 2 successfully flew from Maharashtra across the Arabian Sea to Somalia and then travelled through Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique on its way to Johannesburg.

Why Amur Falcons Choose India

Even though Amur Falcons range across Siberia and East Asia and number more than a million, they choose northeastern India for a very specific reason. The region is rich in termites, which provide the high nutrition needed for the long-distance Amur Falcon migration. This makes India one of the most important stopover points along their migration route.

The story of Amur Falcons, their incredible endurance and India’s conservation success highlights how community participation and dedicated protection efforts can create a global conservation model.